Just standing in Queen Victoria’s bed chamber in Kensington Palace, two centuries after she was born here, I feel swept back in time – little seems to have changed. The floor-to-ceiling windows still look out over green fields and water as far as the eye can see; the floral wallpaper, while not the original, was chosen by Queen Mary to reflect it.

Oddest of all, in this same building, a clutch of dukes, duchesses and princesses, not to mention Prince William and his young family, are co-existing more or less happily in what must surely be the world’s most aristocratic apartment block. A Jacobean mansion, originally extended by Christopher Wren for William and Mary, it is conveniently located a stone’s throw from the buses and boutiques of Kensington High Street.

This was, most famously, the home of Diana, Princess of Wales, becoming a place of pilgrimage after her fatal car crash in 1997, with mourners coming from around the globe to add their tributes to the sea of bouquets piled up before its gates. (Subsequently, her apartment was stripped of its furnishings and left as a shell for years; no wonder when Prince William decided to make his own home there, he chose Princess Margaret’s former apartments instead.)

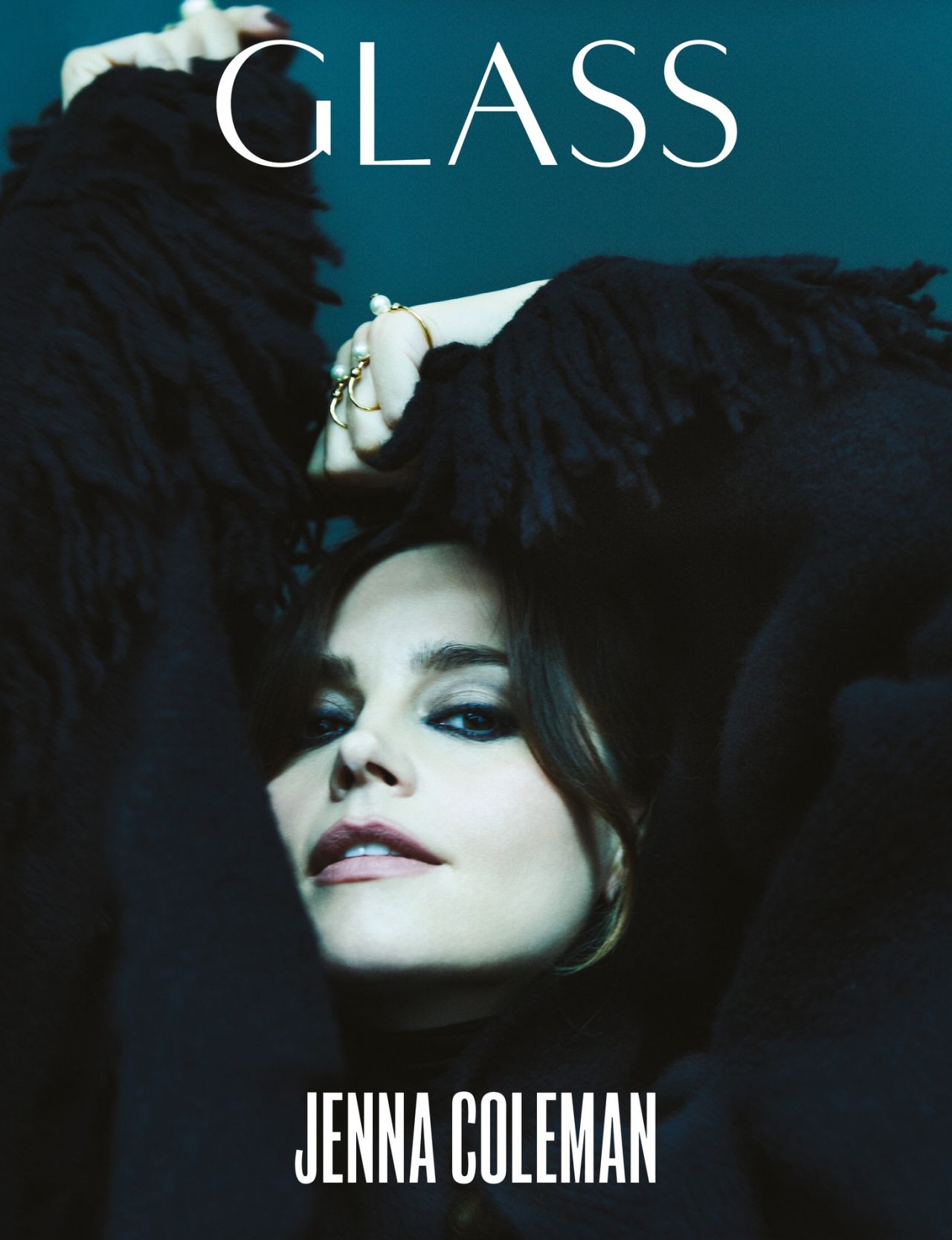

At the moment, however, my attention is focused on the young woman who has just entered the room, escorted by a retinue of security guards, dressers and ladies-in-waiting. She’s tiny as a fairy and exquisitely dressed in full-length brocade and twinkling diamonds… Only the trace of Lancashire in Jenna Coleman’s low voice dispels the illusion that the monarch has returned in person to her childhood home.

These are difficult times for ardent republicans, with both The Crown and Victoria drawing huge audiences across the globe. In the case of Victoria, the series’ appeal is down to a combination of Coleman’s beguiling portrayal and Daisy Goodwin’s lively script, which have together comprehensively recast the Queen’s image. Rather than the dour, repressive widow whose matronly form is immortalised in municipal statuary across her former empire, we are admitted into the presence of a youthful, beautiful and deliciously impulsive creature, whose struggles to ‘have it all’ – an all-consuming job, time with her young family and a meaningful relationship with a spouse whose own ego is threatened by her status – seem utterly contemporary.

This appealing interpretation is no mere populist fantasy, though with her wide hazel eyes, dramatic brows and delicate features, Coleman is a good deal prettier than Victoria ever was. She is impressively dedicated to portraying the role as accurately as possible, goes to Kensington Palace “whenever I can”, and obsessively scours biographies and the Queen’s own diaries for clues to her personality. Queen Victoria’s own drawings are her favourite

source of inspiration. “You really feel that you are seeing the world through her eyes. Everything else has been edited – even her diaries, which were cut by her daughter.“During our shoot, Coleman asks to be shown the exact route that the 18-year-old Princess, clad in her dressing gown, walked from her bedroom to the King’s Gallery to be formally notified by Lord Conyngham and the Archbishop of Canterbury of her accession to the throne. “One day, she’s not trusted to walk down the stairs by herself, the next day she’s the most powerful woman in the world,” she marvels.

It has undoubtedly assisted the realism of the actress’ performance that she is a dainty 5’2” (although that’s still three inches taller than Victoria was) – and thus accustomed to being the shortest adult in the room. “Daisy did say that was why they cast me,” she says, laughing self-deprecatingly. “I can empathise with that feeling of it being harder to project power. For the first series, I was put into cream dresses and bonnets – and I hated wearing a bonnet! I felt really young and girlie. Then I realised that was exactly how Victoria must have felt, surrounded by men in black suits, and having to lead.“

So what is the secret of projecting regal authority? “What I’ve learnt about playing power is, you don’t have to,” she says, wisely. “We had a royal adviser in for a few days, and he didn’t give any notes to me. He just said to the others, ‘You have to imagine there’s an aura round this person.’ That’s the only way you can ever capture it, I suppose.“

Despite her dedication and all the critical acclaim, Coleman appears convinced that Victoria would not have been amused by her interpretation. ‘She’d say that everything I did was wrong, and I’d get a pamphlet full of notes,’ she says. The last time she was in Victoria’s bedchamber, filming an interview for ITV News, she mentions she ‘had a funny turn’ and ended up having to lie with her legs above her head to recover, which she jokes was down to the Queen’s disapproving spirit urging her to be gone.

The new series begins in 1848, as turbulent an era for Europe as our own. Indeed, it may be some consolation, as the torturous Brexit process unfolds, to be reminded of a time when France, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Denmark and Poland were all rocked by popular revolutions, and only Britain remained relatively stable. The fear, however, was that the working-class Chartist movement, which called for democratic reforms including universal male suffrage (at the time, only property-owning men could vote, and it would be 70 years before any woman was given the right), would spark similar political violence and social upheaval.

In this febrile atmosphere, the arrival in England of the newly deposed King Louis Philippe of France, seeking refuge at Buckingham Palace, was seen as dangerously provocative by Victoria’s advisers. “I’ve read her diaries from her perspective of seeing him, and thinking, “Wow, this could be me.” She had a bit of an identity crisis,” says Coleman. “Her attitude had always been: this is my path, this is my life, this is what I’ve been born into.” Here, by contrast, was proof that destiny could be overthrown.

Then as now, the monarchy’s popularity peaked and troughed, with a royal baby bringing a reliable boost to approval ratings. Then as now, too, there were scandals about press invasion of privacy. In Victoria’s case, a collection of private etchings, drawn by herself and Prince Albert and showing the Queen in what she feared was an unsuitably homely role with her children, was acquired by a reporter – another episode explored in the forthcoming series. “She was mortified, and thought it would damage the image she cultivated of a person to be taken seriously,” says Coleman.

In fact, the reverse was true. After the scandals of the preceding eras – Victoria’s immediate predecessor, William IV, had 10 illegitimate children with the actress Dorothea Jordan – it was seen as a refreshing novelty to have a monarch who was an exemplary model of uxorious fidelity. “The Victorian era being strait-laced and buttoned-up is the first thing anyone thinks about, but really that was Albert. He came from a broken home, and it was he who was keen on the morals, and because Victoria was so in love with him she would go along with him – but only up to a certain point,” says Coleman, who describes the Queen as ‘passionate and romantic’, and an open-minded, surprisingly un-hierarchical person.

“She was always curious. When she was younger, on one of her summer holidays, she met a family of gypsies and drew them all and was fascinated by the way they looked, and the way they were a family unit; and then again, there was her friendship with Abdul Karim, and with John Brown,” she goes on, referring to the Queen’s close relationships with two of her male attendants, which were scandalous at the time. “She wasn’t a snob; she was very human and craved anything that really touched her.” The People’s Princess of her day? “I think she was; and very much the Mother of the Nation.“

A few weeks after our shoot, we meet again, this time in a buzzy Sloane Square café. Today, Coleman looks like a different creature entirely: tousle-haired and glowing, wearing an up-to-the-minute ensemble of Blazé Milano tweed coat and Simone Rocha oral dress. She’s just off the plane from Mexico, where she has been taking a well-deserved break, following last year’s intensive schedule, which involved back-to-back filming for Victoria and BBC One’s tense thriller The Cry, in which she played a mother coping with the mysterious abduction of her baby.

It occurs to me that I’ve never seen Coleman with a tan before, since a porcelain complexion is naturally required for Victoria, and she sported a weary pallor as Joanna, The Cry’s postnatally depressed protagonist. “I’ve become a master of swim-suits with polonecks and long arms,” she agrees. “Otherwise you have to spend an extra half an hour in make-up being air-brushed.” Clearly, there are upsides to throwing off the corset, at least temporarily.

April sees Coleman turn her talents to a very different role, as she takes to the stage (appropriately, at the Old Vic) to perform alongside Sally Field and Bill Pullman in

Arthur Miller’s searing drama All My Sons. Hers is the supporting role of Ann Deever, a young woman hiding a dark truth about her deceased fiancé. “I went for the part because of the nuance,” says Coleman. “Things appear a certain way, but underneath, there are politics and family dynamics and push and pull… I think that’s actually why I love period drama so much – because it’s about humanity versus social conventions, and beneath the surface there are all these secrets and lies.“It will be her first time on stage since appearing at the Edinburgh Fringe 18 years ago. “I’ve definitely got the fear. But it’s the good fear you get when you’re excited by something, and not quite sure you can do it.” The relentlessness of the nightly performance schedule does not daunt her in the least. “People keep saying it’s really tough, but after doing 14-hour days for 10 months absolutely straight…“

Following that, Coleman plans to fly to LA in the hope of securing new film roles. “I’d really love to do some shorter jobs, and move between different periods.” She would also like to try her hand at writing or adapting a more personal story, based on her grandfather, who was born in Edinburgh but came to Blackpool in his twenties to run a hoop-la stall on the promenade – which he still does today.

Coleman’s career seems to have been a seamless progression of hits, starting when she was a teenager with a long-running role in the rustic soap Emmerdale, then as companion to the 11th and 12th Doctors in the Doctor Who series, before she embarked on Victoria. And aside from the time that she was asked to attend an audition in a bikini – ‘so I just didn’t go’ – she seems to have escaped the objectification and belittlement highlighted by the #MeToo campaign. “I’ve never had that experience,” she says.

“But I love the fact that there’s this feeling of sisterhood now, and people are talking, it feels like a lot more of an open forum. Daisy Goodwin on Victoria and Claire Mundell on The Cry have both been amazing, supportive figures in my life. And from his first day [as the Doctor], Peter Capaldi made me feel completely equal – he’s such an incredible man. I felt so enabled by him.“

Her workload would leave Coleman little time for conducting a personal life, were it not for the fact that, fortunately and serendipitously, her long-term partner is the handsome Tom Hughes, who plays Prince Albert, so they are able to spend a good deal of time together on set.

Thus far, their relationship has been conducted with positively Victorian discretion; they never talk about one another, and when I ask Coleman if she’s engaged, she simply waves her ringless fingers at me in response. (The following week, I meet them both at the gala opening of the Dior exhibition, and have the somewhat surreal experience of talking to Victoria and Albert at the Victoria and Albert. It does not escape my notice that they politely, yet firmly, refuse to be photographed together… “I think it’s been very wise not to speak about it,” Coleman tells me.)

Meanwhile, she has moved into a new home in Islington, and is revelling in doing it up. “I’m very nesty,” she says. “I like patterns and textures and velvets. Books make me feel grounded. And just walking out of the door to get a coffee in the morning – the luxury of free time.

“I love touching base with normal life. I worked out that last year, I literally spent more time in other people’s clothes than in my own, but you’ve got to look after your own life, too, so you can come to work and bring some sense of reality to it.“

Having worn multiple pregnancy bumps of different sizes, screamed through several labour scenes and devastatingly interpreted the exhaustion and loneliness of new motherhood in recent months, she is understandably in no hurry to experience it off-screen.

“That’s probably opened up my mind to the realities,” she says. “Half of my friends have babies, and half don’t, so it doesn’t feel like a pressure. I want to take my time. There’s a whole lot more of the world for me to see first. I’d love to have children one day. But not nine of them,” she concludes, with a distinctly un-regal grin. “I can tell you that as a fact.“

‘Victoria’ returns to ITV later this year. ‘All My Sons’ is at the Old Vic from 13 April to 8 June, and will be broadcast live to cinemas around the UK on 14 May as part of National Theatre Live.

Harper’s Bazaar UK

Navigating the majestic surroundings of Kensington Palace, Jenna Coleman follows in the footsteps of the monarch she portrays in Victoria. As its new series begins, she speaks to Lydia Slater about her search for clues to understand the secret life of the sovereign.

Check the pictures in our gallery:

Magazine Scans > 2019 > #001 Harper’s Bazaar UK (April 2019)

Photoshoots > 2019 > #005 Harper’s Bazaar UK